Postdoctoral Researcher Matti La Mela: Finnish IP developed in relation to other countries

05.06.2019June 5, 2019

Matti La Mela, Postdoctoral Researcher at Aalto University, is a walking IP history book who knows the stages of intellectual property rights down to the roots. La Mela also knows the answer to whether anything has changed in the last 200 years.

“The background included censorship and keeping secrets”

If the patent attorneys from the 1800s and present day were sitting at the same table, they would speak the same language. They would have similar thoughts about commercial interests and how the inventor and the idea are entitled to protection. At the same time, however, there is a need to barter with others: inventions cannot be protected for too long. The inventor has received training and made the discoveries as part of society at the time. That is why it is important that others can also benefit from the invention.

The change in the understanding of IP and protection over the centuries is fascinating. How did we end up in a situation where intellectual work is seen as property? Why did we start to think that inventions involve a creator’s own idea that must be protected?

The essence of Finnish copyright developed inconspicuously in administration. In addition to commercial interest, the ultimate reason for protection has lied in, for example, keeping trade secrets. Our first paragraph of modern copyright law was created as a by-product of censorship legislation in 1829. The same need for control applies to the early stages of protecting inventions and the roots of patent law. Patents were the privileges and rights that a ruler gave to an inventor if the inventor started to practice a branch of industry. The object of the protection was machines and book, but its motives were censorship and administrative control.

“Art was central to the development of copyrights”

In my work as a postdoctoral researcher and in my dissertation, I have studied the history of proprietary rights. Industrial property rights and trademarks have been protected since ancient times when products and goods were labelled with the craftsman’s stamp. Trade secrets passed from the master to the apprentices, such as the professional skill of glassblowers in Italy, were also intellectual property protection.

The thing that led the way to the current intellectual property rights in Finland was a public debate beginning internationally in the late 1700s that focused on an individual’s right to the fruits of his or her intellectual work. Technical development and new ways of copying also posed challenges. The debate was multifaceted and the principles developed over the century. Art was a key area in the development of copyrights: with art, we are confronted with questions about what is an original work, how does its authorship manifest itself, what it means to copy a work by painting or later by photographing.

“The current IP tradition was established in the 19th century with the support of the Nordic countries”

The 1860s and 1870s were significant for Finnish intellectual property rights. At that time, there was debate in Finland both in the press and in parliament when disputes about freedom of expression and censorship, which also relate to copyrights, emerged. As industrial activity picked up, there was also a need kind of practical need for industrial property rights.

These two decades were the period during which it was determined where the Finnish tradition of intellectual property rights stands. We were part of the Russian Empire, so our environment could have developed in another direction because of the Russian tradition of law-making. However, Finland anchored itself strongly in the Nordic and Western traditions. For example, our first patent decree from 1876 was a word for word copy of an equivalent decree in Sweden. Close cooperation is evident here throughout history in Nordic legal tradition, patent legislations that have developed in a similar direction with each other, business as well as close cooperation and networking between Nordic attorneys.

“Rudolf Kolster – the father of all patent attorneys”

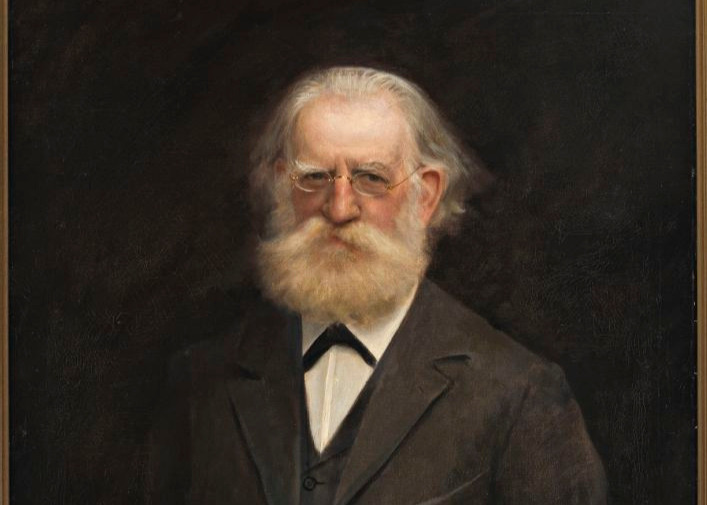

Rudolf Kolster (1837-1901), Gallery Rauno Träskelin, Aalto University archive, CC-BY 4.0.

The role of patent attorneys in backing inventors has been major. They have helped inventors define and describe their ideas on paper and specify what each invention is about. Patent attorneys have helped put new things into words in such a form that they are compatible with existing IP principles but are protected as new ideas as well as possible.

The first significant patent attorney in Finland was Rudolf Kolster, whose role in the development of the patent industry is central. Kolster, a multi-talented person with a German background, was recruited to Finland as a polytechnic teacher. He acted as a patent attorney in addition to his work as a teacher and engineer.

Kolster served as an expert on legislative committees and advised patent authorities with novelty examinations, was involved in organisations, wrote in papers, travelled to foreign events and gathering of the industry and maintained an international profile thanks to his overseas clientele and many international contacts.

Kolster’s influence on the Finnish IP field is still present today: both Rudolf and his sons have contributed to the professionalisation of the IP environment and operations in Finland. Rudolf Kolster modified the early principles of patent operations through his international knowledge. He influenced Finland’s first patent act in legislative committee work, and through the system of attorney organisations, the father and son have been involved in discussing and forming the principles of the profession.

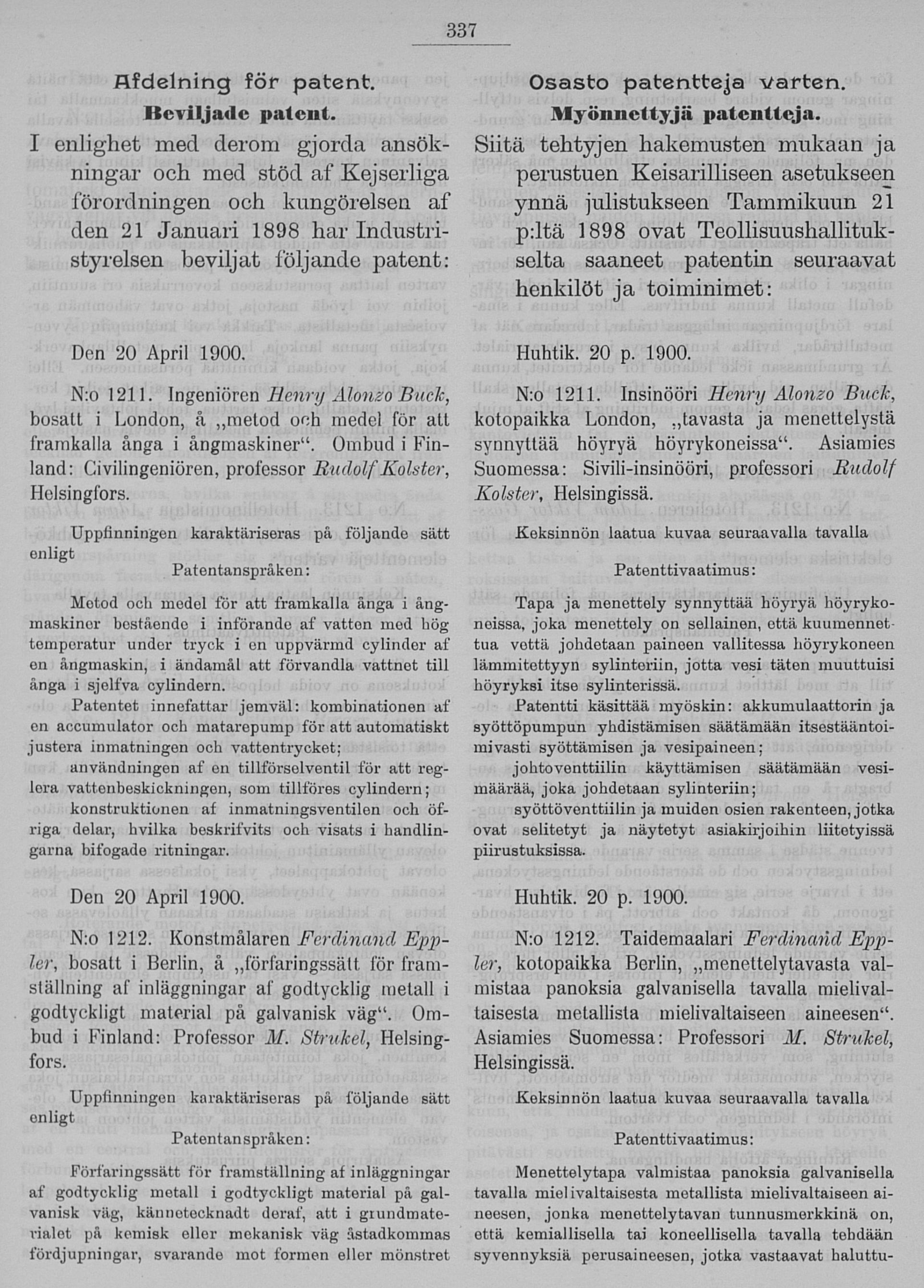

Digital collections of the National Library of Finland, 17.8.1900.

“The discussion on internationalisation has been going on for 200 years”

Common international legislation that states would be subordinate to was discussed in Finland as early as in the late 1800s: copyrights would be protected at a national level through general agreements while also committing to certain common principles. Consideration was given to granting protection to works by Swedish authors in Finland in the 1840s and a common Nordic patent law to protect writers and artists was discussed 30 years later. This discussion on internationalisation has been going on for 200 years already, so it is surprising that nation states have maintained their strong role for such a long time.

Another notable point is how the eagerness to protect varied according to the countries’ own interests. This was not just about economic issues, but about justice and fair treatment between countries, as is the case today as well. We can now criticise others for failing to comply with copyrights, but in the late 1800s, Finland was reluctant to join international agreements on literary and artistic rights. The works of foreign authors were translated and published without obligations until the 1920s. Permission may have been enquired and compensation paid as well, and international authors were generally not against translation as the Finnish language was considered marginal. The issue was commercially oriented for publishers, but the wider debate also touched on the educational opportunities of a poor northern country.

Intellectual property rights have always been challenged and questioned. It would be entirely possible for us to have no patent protection. In the mid-19th century, there was a very strong movement against patents. Patent protection was seen as an unnecessary step, a better option for which would be a system of free trade. In the 1870s, international trade and tightening customs policies gave rise to a desire to protect one’s own rights more, after which patent protection was widely accepted.

“The principle of transparency has been reflected in patenting for centuries”

The long traditions of openness and transparency in the governance of Nordic countries are also reflected in the principles of patenting. As early as in the 19th century, patent applications and descriptions were recorded in paper form, new patents were published in the press and their drawings and designs were on display for everyone. This is continuing also in the digital age: All Finnish patents since the early days have been digitised in the Espacenet database. The availability of patent information on an international scale encourages new ideas and helps to evaluate what has already been invented in a particular area and what could still be developed.

We have gained new tools and all information is openly available and comparable. Artificial Intelligence allows us to consider the similarity of texts and other works, so the identification of plagiarism is in some sense easier. Authorities, on the other can, can speed up and improve their evaluation processes and novelty examinations.

Keeping up with social changes is the be all and end all in the field of intellectual property protection. New types of works, media and sectors of technology have forced the field of intellectual property rights to respond to the new challenges posed by the development of society. When new kinds of intellectual work and property emerge, there is also new debate about protection. Today, the biggest challenges relate to maintaining free access to information, digital products and technological development in a digital environment.

Patent 342 (Ludwig Bernhard), a wood cutting machine from year 1889. Ruldof Kolster acted as patent attorney for this invention. Espacenet.com

Polytechnic College building next to Hietalahti market square, year 1886, Aalto University archive. The Polytechnic College, which also housed the patent office at the end of the 19th century, was a concentration of technical knowledge and patent expertise.

READ MORE

Celebrating 145 Years of Kolster